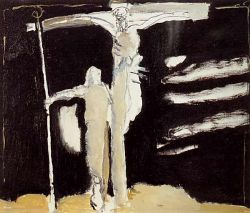

Death and faith

A lexicon of the inner life

by ENZO BIANCHI

Christian faith is also a great battle against death, and above all against the fear of death

"The modern world has managed to debase the thing that is perhaps more difficult to debase than anything else, because it has a singular dignity: death." This observation by Charles Péguy (1907) gave Theodor W. Adorno matter for reflection in his Minima moralia. It gives us reason to reflect as well, we in the West who, almost a century later, see death repressed and at the same time flamboyantly exhibited, made obscene - in other words, banished from the land of the living, estranged from the world of social relationships - and at the same time turned into a spectacle and mercilessly exposed, as if in a media-officiated ritual of mass exorcism. A narcissistic society attempts to repress everything that reminds it of its limits, and in particular the event of death, which has the power to annihilate every human delusion of omnipotence. Yet in carrying out this anesthetic operation we forget that we are depriving ourselves of the reality that, more than any other, helps us understand ourselves, because it places life's 'big questions' in front of us; the enigma that, in its irreducibility, can become a revelation, open up glimpses of meaning for our life, and above all, bring us out of the banality and mediocrity in which we often enclose ourselves. "When a person wants to understand himself, he must question himself about death" (E. Jüngel) - we should open ourselves to the scandalous power of the question death asks and is. By forgetting death or trying to conceal it, we contribute to the dehumanization of a culture and a society.

How can we forget that it was when the Buddha saw a dead person and became aware of the reality of death (he had already become aware of the reality of illness and old age) that his initiation into the way of illumination began? As a young prince, the Buddha had always lived in royal palaces where, under his father's protection, he had been prevented from seeing the world's evil, but he found it necessary to break through the barrier that held him back from a direct encounter with the reality of the human condition.

Memento mori, the remembrance of death, is as relevant now as it has ever been! Christians, who know that the event of the death and resurrection of their Lord is at the heart of their faith, have the responsibility and diakonia of keeping the memoria mortis alive in the world - not because they are cynical, have morbid tastes, or hold life in contempt, but in order to give life weight and significance. Only those who have a reason to die also have reasons to live! And only those who learn to lose, to accept the limitations of their existence, know how to accept death as a friend. The death of Christ teaches us how to die and how to live. In the Gospels Christ's death is not presented as a fact, a destiny passively endured, but rather as an act, the culminating event of a life.

It is a death brought to life by love - God's love for humanity, the divine passion of love that becomes a passion of suffering in the Son's death for love. The way we experience death is connected to our experience of the death of the people we love - with their death, something in us also dies. And if love is what gives life its meaning, it also leads us to the point of considering the loss of our life for someone we love an 'obvious and logical' consequence of our love. We understand something about death, and suffer the consequences of death, to the extent that we love, but death is also capable of bringing our loves to an end, cutting them short from one moment to the next. We see death as more foreign and alienating than anything else, yet it is also what is most truly and originally ours, so much so that, in today's hospitals, the denial of death to those who are on the point of death is simply inhuman. Today, as Norbert Elias has noted, people die much more hygienically, but also much more alone, than they did in the past.

Christians, who place their faith not in immortality but in resurrection from death, know that their faith does not sidestep the grief of death but passes through it. They also know that God has taken upon himself the dramatic separation of death, and that death is not only an end but a fulfillment. We can learn to make death an 'act' in prayer, because prayer means giving time to God, and time is life.

It is above all in prayer that death, our 'enemy,' can be experienced as life for God and with God, and can thus become our 'sister.' There is a wisdom that comes from 'counting our days' (cf. Psalm 90:12) - in other words, accepting with serenity the limited number of days we are given in which to live, the dimension of temporality, and death. We can arrive at this peaceful acceptance by founding our lives on our faith in God, who called us to life and, in the same way, calls us to himself through death: "You turn humans back to dust, saying, 'Return, sons of Adam!'" (Psalm 90:3).

Christian faith is also a great battle against death, and above all against the fear of death that makes men and women "subject to slavery all their life" (Hebrews 2:15). This battle against death is not an act of repression; it is a battle because death still shows the face of an enemy and an antagonist, and it is a battle in Christ, because many of the strategies we use in an attempt to escape the anxiety of death follow the logic of idolatry and sin. We are sustained in this battle by our faith that it is not death that will have the last word, but God himself and his love, the love that leads us through death to eternal life.