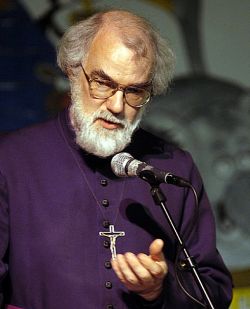

Message from Rowan Williams, archbishop of Canterbury

Bose, 7-10 September 2011

XIX International Ecumenical Conference

on Orthodox spirituality

It's often been observed that the liturgy of the reformed Church of England laid exceptional stress on the daily office

The Word of God in Anglican Tradition

In the time available today, I can’t begin to offer a comprehensive survey of what Anglicans have thought about hearing and meditating on God’s word across the centuries; that would need a book at least. But what I’ll try to do is to introduce you to a few of the great doctors of the Anglican tradition and to the thoughts they have about what is most important in the discussions of this meeting, the transforming grace that comes in the reading of Scripture.

It’s often been observed that the liturgy of the reformed Church of England laid exceptional stress on the daily office. The orders for Morning and Evening Prayer in the English Prayer Books, from 1549 onwards, represented a careful weaving together of elements from the sevenfold monastic office – psalms, canticles, responses and passages from Scripture – into two coherent units which guaranteed that the Psalms would all be said in the course of a month and that substantial portions of the Bible would be read each day in a manner which ensured that most of the text of Scripture would be covered in some sort of order. In other words, from the start, the Church of England took it for granted that the encounter with the ‘Word of God written’ was one that took place within the daily sacrifice of praise offered by the community. Archbishop Cranmer, defending the English Prayer Book, wrote in 1549 that ‘in the English service appointed to be read there is nothing else but the eternal Word of God’. And the point of reading Scripture in this context was to provoke the self-awareness that led to repentance and made us fit to receive the sacrament (Folger: Richard Hooker, 195). Put another way, the purpose of reading Scripture was that we should receive God’s wisdom: Scripture is not a book that gives us simply information, it introduces us into the mind of the maker. To the extent that it is a witness to and an effective communication of the eternal word who is Christ, the Wisdom of God (I Cor.I.24), it seeks to bring us into harmony with wisdom. The greatest Anglican theologian of the immediate post-Reformation period, Richard Hooker, takes up the phrase from II. Tim. 3.15 about scripture making us ‘wise unto salvation’ and sets it alongside the end of John 20, ‘These things are written that ye might believe that Jesus is Christ the Son of God’ (Laws I.14.4): Scripture puts before us the way to life and the laws by which we may find ourselves in harmony with God. ‘The principal intent of Scripture is to deliver the laws of duties supernatural’ (ibid. 14.1). And Hooker emphasises this dimension of wisdom and ‘supernatural’ law, so as to avoid the narrow perspective of his opponents who are claiming that Scripture is essentially a law-book that will solve all practical issues of discipline and practice in the Church today. Against this, Hooker argues very strongly that Scripture contains ‘everything necessary to salvation’ in the sense that it provides what we need to know and could not otherwise find out – not that it is an encyclopaedia of all that could possibly be truly said about God (ibid.).