Research project and scientific committee

XIX International Ecumenical Conference

on Orthodox spirituality

in collaboration with the Orthodox Churches

The questions that arise touch in depth some of the great interrogatives open still today before every man: how does Scripture shape the spiritual life? How does it inspire decisions (personal/community)?

XIX International Ecumenical Conference

on Orthodox spirituality

Bose, Wednesday 7 - Saturday 10 September 2011

in collaboration with the Orthodox Churches

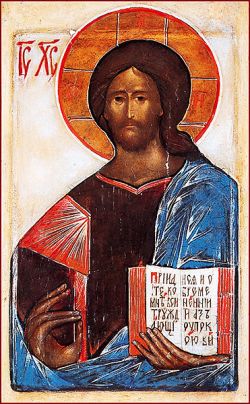

THE WORD OF GOD

IN THE SPIRITUAL LIFE

In the tradition of the undivided Church, Holy Scriptures and the Word of God that they contain have always been the living fount of the believer’s spiritual life, of life according to the Spirit. The Word of God lives in the baptized, the Holy Spirit nourishes in us this divine life and makes it grow. The fathers very soon applied to Scripture itself the words that the Gospel uses of the Kingdom of God. “The Word of God,” writes Maximus the Confessor, “is similar to a mustard-seed, it appears quite small before being cultivated. But when it has been cultivated it embraces the meaning of all beings” (On theology, II.10). This is the hermeneutical principle that Gregory the Great, known in the East as Gregory of the Dialogue, expresses with the formula Scriptura crescit cum legente: the understanding of Scripture increases with the spiritual maturing of the person who reads and interprets it (cf. Homilies on Ezechiel, I, SC 327:244–245).

Reading the Scriptures, however, especially in the Eastern Churches, is always a reading in the Spirit, hence also in the community of believers gathered together by the same Spirit, in a living unity of carrying out the commandments, prayer, and the giving of thanks in the liturgy. Lectio divina is a meeting with a living person, with God himself who speaks and because of this, according to the fathers, it presupposes a certain level of spiritual maturity and cannot be loosed from a life of asceticism totally oriented towards God. “Whatever you do, base yourself on the testimony of the Holy Scriptures,” said Antony, the father of monastics (Alphabetical series, Antony 3).

The words of Scripture are spirit and life (Jn 6,63), the knowledge that flows from Scripture is “the Spirit’s teaching” (en didaktois pneumatos), it is knowledge by revelation (Mt 11,25–27) and is the fruit of spiritual interpretation. Scripture itself refers the reader to the Holy Spirit as its proper hermeneutical principle. “It is in [Scripture] that the Spirit is understood,” writes Maximus the Confessor; Scripture is the principle of transfiguration, of divinization (On theology, I.97). “It is the oil of the divine Spirit, which anoints the soul and renders it soft and humble” (Nicetas Stethatos, Physical chapters, 90).

We can, then, understand the other great hermeneutical principle of the fathers, for whom Scripture is “the interpreter of itself” (Gregory the Great), a principle that remains constant in the whole of tradition. “Whoever seeks the end of Scripture has for his teacher, as the great Basil and Saint John Chrysostom say, Scripture itself” (Pete Damascene). As a monk of the West who had drunk of the Eastern founts, William of Saint-Thierry (ca. 1075–1148), writes, “it is necessary to read the Scriptures with the same Spirit with which they were written and it is also necessary to understand them with the same Spirit” (Epistola ad fratres de Monte Dei, I.10.31).

The gift of the Spirit confers on the disciples understanding of the words of Scripture and of Jesus himself: the Comforter, the Holy Spirit whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you every thing and will remind you of all that I have told you (Jn 14,26). At the other extreme of tradition, the Russian bishop Mixail (Gribanovskij, †1898), in commenting on this verse of the fourth Gospel, writes: “The events narrated by the Gospels are transmitted to the reader’s spirit in a living manner, that is, by the same Holy Spirit. Thus we can understand the Gospel’s living divine action on the souls of those who read. In the Gospel accounts there lives the same divine force of the Holy Spirit who presided over the events of the Lord’s early life: in them there speaks a creative power that saves us” (Nad Evangeliem, 116).

The XIXth International ecumenical conference on Orthodox spirituality (Bose, 7–10 September 2011) desires to propose for its theme this essential unity of Holy Scripture and exegesis in the Spirit, the Word of God and spiritual life, which runs through the entire tradition of the Eastern Churches, in ways and forms different from those of the West, but with a strong convergence on the pneumatic reality of Scripture, as Vatican Council II has also highlighted.

Without claiming to exhaust all the wealth of this tradition, the conference desires to concentrate on three focal aspects, transverse to the various relations.

A first aspect will be dedicated to the hermeneutics of the Bible as elaborated by the fathers, who touch on problems that remain still today of great topical interest: the meaning of the different literary genres; the relation between exegesis, praxis, and spiritual experience; the ecclesial meaning of Scripture; the living relation between faith and Word.

A second aspect will be centered around the ecclesial dimension of the Word of God. The Holy Spirit, making fruitful the Scriptures in the Church’s bosom, reveals Christ’s face, leads towards the encounter with him, and orientates personal and community existences towards a life in obedience to the Word that emerged from “it is written”. “Through the Word of God the entire holy Church remains in faith, is confirmed and saved through the help of him who spoke through the prophets and the apostles” (St Tixon of Zadonsk, Tvorenija, 1:180). In this sense not only will there be reflection on the tradition of the past, but also on the present of the various Churches, so as to permit a proper approach to how the Eastern Churches in their spiritual tradition and in the life of the people of God have always preserved and lived in many ways Holy Scripture: from the liturgical celebration to the importance of the Bible for Orthodox theology, from a historical and critical exegesis to the ecclesial reading of the Bible, to the relation between exegesis and spiritual life.

Scripture itself is polyphonic: a multiform tradition flows out of the very plurality of the Biblical text. The translation of the Gospels marks the birth of a Church, of a spiritual tradition, and of a particular hermeneutics. Often the Biblical renewal in a Church coincides with a spiritual renewal. The third aspect, thus, explores the reality of Scriptural presence in the various Churches and in particular in the experience of Christian monastics. The questions that arise touch in depth some of the great interrogatives open still today before every man: how does Scripture shape the spiritual life? How does it inspire decisions (personal/community)? how does Scripture interrogate life? Ho does life interrogate Scripture?

SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

Enzo Bianchi (Bose), Lino Breda (Bose), Sabino Chialà (Bose), Hervé Legrand (Parigi), Adalberto Mainardi (Bose), Antonio Rigo (Venezia), Roberto Salizzoni (Torino), Michel Van Parys (Chevetogne)